The Quiet Power of Boredom

We tell children that boredom is good for their imagination. So why do we deny ourselves the same gift?

In our relentless pursuit of productivity, we've neglected the quiet art of idleness. Through the thief of distraction, we steer clear of empty spaces, pauses, and the in-betweens. These precious moments I refer to as the waiting rooms of our minds. The mental departure lounges where we are compelled to sit before taking off on our conceptual flights.

For those shaping the visual landscape, boredom cannot be an enemy. Rather, it ought to be our muse. Boredom allows for a vacuum wherein the mind is free to expand. It is the wellspring of imagination—the blank page before the first word is written, the hush before the frenetic rush of a melody.

When we give ourselves permission to be bored, our mind is allowed to roam, and it is in roaming that we are more likely to stumble across something new.

I’m writing this on my commute to work—a routine of headphones, absorption, and precision so familiar that I could probably make every connection in my sleep. And that’s exactly the problem. I’ve become numb to the differences each day brings, whether subtle or drastic. The whole experience has turned into an hour of nothing when it could be so much more—an opportunity for imagination, for escape. Or simply for looking up.

It is widely known that our imagination flourishes most in childhood—a wonderfully unencumbered time when rules of form and structure hold no sway. I see this in vivid, kaleidoscopic colours with my son, Rudy. As his father, it would be easy to fill each moment of his day with the cheap thrill of a screen, but I've come to understand that he needs room for his imagination to wander. And for this to happen, he must be bored.

Research supports this. Studies highlight that boredom is essential for fostering creativity and imagination in children. Without constant stimulation, they develop stronger problem-solving skills, deeper thinking, and greater independence. Boredom has been shown to spark creative thinking, while excessive screen time is dramatically linked to reducing cognitive development and diminished divergent thinking.

So why, when we apply these boundaries for our children, do we do ourselves a disservice by choosing to ignore them?

The Science of Stillness

Contemporary psychology has long recognised the value of downtime in sparking creativity. Dr Sandi Mann, author of The Upside of Downtime: Why Boredom is Good, holds the opinion that boredom stimulates creativity by forcing our brains to seek internal stimulation. ‘When we’re bored, we’re searching for something to stimulate us that we can’t find in our immediate surroundings,’ In other words, we begin to daydream, which in turn fuels creativity by activating different pathways in the brain. It’s a classic neurological demonstration of a ‘desire path’—the route we carve out for ourselves beyond the expected, well-trodden route. And it’s in that exploration that we’re forced to confront the new.

The Myth of Constant Inspiration

For visual thinkers, creativity is not an infinite tap that flows at will—it needs time to refill. In creative professions, there is a persistent myth that success depends on being endlessly inspired, able to turn-around a mood board within hours of a brief, yet too much input leads to creative paralysis. The relentless flow of social media can become a crutch—something that keeps us feeling ’productive’ without actually being productive.

Designer Stefan Sagmeister often speaks about the importance of downtime. Every seven years, he shuts down his studio for a year to ‘pursue some little experiments, things that are always difficult to accomplish during the regular working year.’ A creative sabbatical that he believes gives space for true innovation.

‘We spend the first 25 years of our lives learning, then 40 years working, and after that, we’re supposed to enjoy our retirement. I thought it would be a good idea to cut off five of those retirement years and distribute them over the working years,’ Sagmeister explains in his TED Talk, The Power of Time Off.

Author Robert Poynton echoes this sentiment in his book Do Pause: You Are Not a To Do List. Poynton emphasises the importance of taking intentional breaks to rejuvenate and gain perspective, discussing the value of longer creative pauses that are vital to recharge creatively and to help us disconnect from stale daily routines.

But it's not very realistic, is it? We can't all take a year off, and it’s unlikely our commitments will allow these capsules of time just to sit, think, and wait for inspiration to come to us. This is where mundanity comes in.

Life is not always a perilous journey into the recesses of our psyche. We are bound by obligations and responsibilities that also vie for our attention. Embracing the mundanity of everyday life can also be creatively fulfilling, and utilised to enhance the art of looking sideways.

A 2013 study published in Frontiers in Psychology found that engaging in simple, repetitive tasks activates the default mode network in the brain. This network is responsible for self-reflection and problem-solving. This explains why some of our best ideas emerge while doing the dishes or taking a shower. By not fully embracing the boredom associated with these tasks, we’re cutting off the power for our default mode to jump-start. These moments are precious, and we should rethink and embrace their existence and importance as part of our daily routines.

Jon Kabat-Zinn, the father of modern mindfulness describes mindfulness as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.” In a world filled with commitments, developing this awareness is nothing short of remarkable. It allows us to truly see the unseen—to notice subtlety in form, colour, pattern, and emotions. Observations that would otherwise pass by unnoticed. To embrace boredom is to embrace mindfulness.

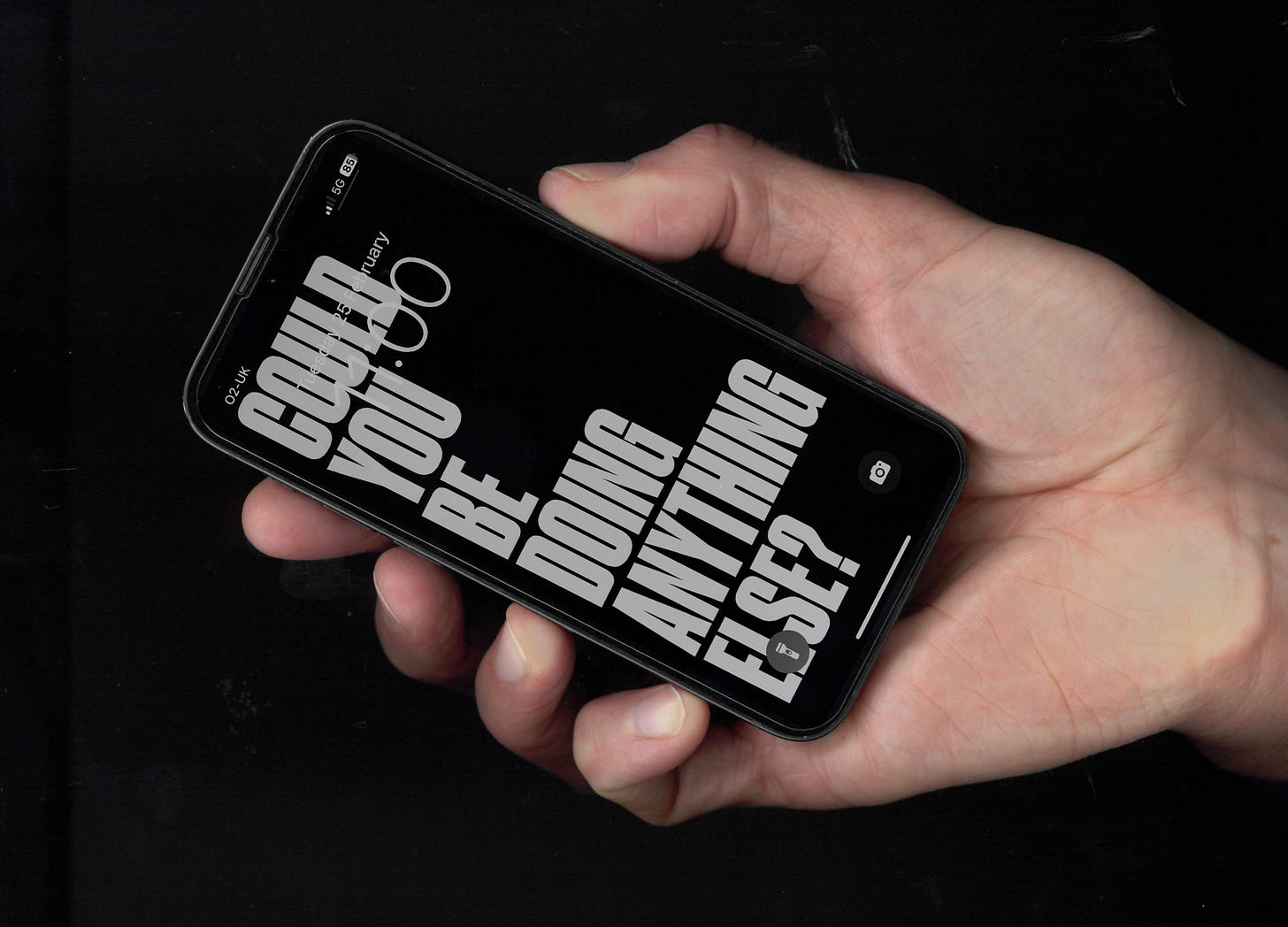

Could You Be Doing Anything Else?

We too often reach for a distraction. It is highly likely you've shifted around your digital network whilst reading this. It's a tactic employed by app creators; they want us numb. They want us addicted. The sense of being present has been lost, and there is a real danger of drifting ourselves into being completely deskilled in creative thinking.

In unguarded moments, I catch myself in an instinctual cycle of updates, rarely pausing to ask if I could be doing something more meaningful. We've become trained to fill each moment with a swipe of our thumb, spending our existence fumbling through life, looking down into the glow of technology. When was the last time you sat through a film, a commute, or a conversation without distraction? We're drawn to the dopamine rush when our devices light up—but that light is artificial, and that artifice is something we, as creatives, are empowered to resist.

Could I be doing anything else? The answer is almost always yes. So much so that I’ve made this question unavoidable, displaying it across all my screens in the hope that it disrupts deeply ingrained habits and forces me to reconsider the relevance of what I’m doing—and what it truly means to remove myself from the present. So next time you feel the urge to reach for your phone in a quiet moment, resist. Don't rush to fill the silence. Sit with it. Let your mind wander. Let stillness sow something new, because sometimes, the best ideas come not from doing—but from simply being.

⊹₊ ⋆

Thank you for the interesting read, Chris. You have quoted one of my favourite authors in your post — Jon Kabat-Zinn. As someone who has studied his work relentlessly, I think boredom actually becomes impossible when we develop mindfulness.

I believe that from a mindfulness perspective boredom happens when we treat the moments in between as waiting rooms—when we believe real life is happening somewhere else. It’s the mind rejecting the present moment, deciding that this moment doesn’t matter.

I wonder what would happen if we treated the in-betweens as small yet meaningful moments. Maybe boredom isn’t something to endure but an invitation to pay attention, to notice the life unfolding in these small moments—the way light shifts in a room, the quiet hum of life continuing around us.

Maybe boredom only exists when we forget that every moment, no matter how small, matters in its own way.

Is boredom in this day and age just really an absence of stimulation? We are just not used to having very little of it and mistake it for boredom, and in fact we should embrace this state, turn inwards and embrace it from time to time.